Baseball History, Origins, Growth and Changes in the Game

Origins: The exact origins of the modern game of baseball are somewhat difficult to track. Ball games have been played throughout the centuries; in America, where baseball originated, the game generally traces its lineage back to some combination of cricket and rounders, two games brought over by European settlers. There is, of course, the popular myth that Abner Doubleday, a Union soldier from the Civil War "invented" or "created" the modern game , but there is no actual proof of this, and Doubleday himself never claimed to have anything to do with the game.

New York Knickerbocker Base Ball Club Rules Set

Though formal rules for "Base ball" can be found as far back as 1838 in Philadelphia, the first set of rules which resemble the game today come from the New York Knickerbocker Base Ball Club, a group of about thirty young men who regularly played the game. The rules they established (which are still used today) include a diamond-shaped field, making the "balk" illegal, introducing foul lines, three strikes-and-out for a batter and that runners must be tagged or thrown out. The first official game played under these rules was on June 19th, 1846 in Hoboken, New Jersey, between the Knickerbockers and the New York Base Ball Club (with the Knickerbockers losing 23-1).

Growth: Growth Of Baseball The spread of the game occurred primarily after the American Civil War. Because cricket required finely cut grounds, it was harder to play the game during the war. Baseball, on the other hand, could be played almost anywhere. Additionally, though the majority of clubs belonged to middle-class merchants, the 1850s and 60s saw the rise of working-class teams, which became the most popular among the fans of the game, most of whom were working-class people themselves.

The National Pastime The first reference to baseball as "the National Pastime" came from the New York Mercury newspaper in 1856, though the title then was a bit premature. Baseball in that time emerged as a New York game played primarily by immigrants. Newcomers to America took to the game by scores, forming their own clubs, while the Knickerbockers continued to refine the game.

First Pro Team Cincinnati Red Stockings The country's first "all-professional" baseball team emerged in 1869, the Cincinnati Red Stockings, financed by a group of Ohio investors. Each player was paid a salary, with the highest paid player, shortstop George Wright, earning $1,400 per season - a value equal to almost $23,000 a year now. However, in 1870, the manager of the team moved it to Boston. A year later, the newly-minted Boston Red Stockings, along with eight other teams from Chicago, Philadelphia, New York, Washington, Troy (New York), Fort Wayne (Indiana), Cleveland and Rockford (Illinois) formed the National Association of Professional Ball Players.

The National and American Leagues:

National League After only five years in existence, the National Association was struggling, and in the winter of 1876, William A. Hulbert, the owner of the Chicago White Stockings, poached five of the best players in the league from two of the other teams, and formed the National League, along with teams from Boston, Cincinnati, St. Louis, Hartford, New York, Philadelphia and Louisville. Owners ruled the league with an iron fist; players who complained about salaries were fired, and often blacklisted. One of the first documented cases of gambling in the game occurred only a year later, when, in 1877, four members of the Louisville Grays were found to have thrown games on purpose, paid by gamblers to do so. The players said it was because their owners had not paid them.

Base ball As A Business However, with the death of Hulbert, A.G. Spalding, his second-in-command, became president of the White Stockings, and ushered in what could arguably be called the true beginning of the game . Spalding insisted the players be paid like entertainers; he created Spalding Sporting Goods, manufacturing balls, caps, uniforms and gloves. Spalding (whose brand is still used to this day), it is said, created the business of baseball.

Major League Baseball Born Though two other leagues, the American Association and Player's League, tried to challenge the National League for dominance, the NL largely kept baseball a monopoly - that is, until the turn of the century. In 1900, Byron "Ban" Johnson created the American League out of four teams, picking up unemployed ballplayers and raiding National League rosters. As more and more players moved to the American League (including Cy Young, the winningest pitcher of all time), the National League owners were forced to submit. In 1903, a National Agreement was set up, creating a National Baseball Commission - made up of the president of each league and a permanent chairman - that would govern the game . Major League Baseball was born. That fall, in October of 1903, the game's first "World's Series" was played, with Boston (from the American League) beating Pittsburgh, their National League counterparts.

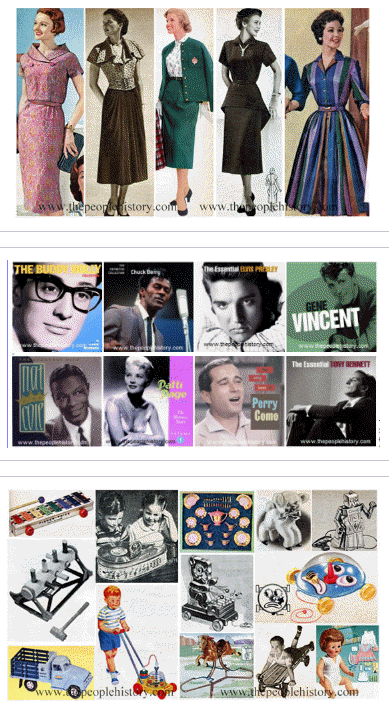

1950s Prices including inflation prices for homes, wages etc,

Baby Boomers raise families following 20 years of unrest ( Great Depression and World War II ) the peak of the Baby Boomer Years

Includes Music, Fashion, Prices, News for each Year, Popular Culture, Technology and More.

The Game's Early Stars:

Cy Young Between the National League and the emergence of the American League, baseball's growing popularity helped introduce some of the game's first stars, names that live on in baseball lore. When Hulbert formed the National League by poaching other players, one of those players was Cap Anson, still third on baseball's all time Runs Batted In (RBI) list. One of the star pitchers in the first "World's Series" in 1903 was a man named Denton True Young, though his nickname, "Cy," is more commonly known to fans today. Baseball's all-time leader in wins, losses, games started, innings pitched and complete games has the annual award given to the best pitcher in each league named for him, the Cy Young award. It's important to note, however, that when Young was pitching, the notion of relief pitchers hadn't really been introduced. Of the 815 games he started in his career, Young finished 749; compare that to the most recent player on the all-time games started list, Greg Maddux: he started 740 games in his career (fourth all-time), but pitched only 109 complete games. It's assumed no one will ever beat Young's records.

Ty Cobb and Honus Wagner The 1909 World Series between Pittsburgh and Detroit was, at the time, thought by many to settle the argument of greatest ballplayer, a contest between two ballplayers named Tyrus Cobb and John Peter Wagner, known today as Ty Cobb and Honus Wagner. In the series, Wagner outhit Cobb, in addition to compiling more stolen bases and winning the title. Many of their contemporaries later said Wagner was the best they'd ever seen, better than Cobb; Ty's drawback was his personality and playing style - one of the most hated men on or off the field in baseball history, Cobb was regularly referred to as "the dirtiest player in baseball." Historical stats, however, back up Cobb: the Detroit outfielder still holds the record for highest career batting average, hitting .367 lifetime. He's second all-time in runs, hits and triples, and fourth in stolen bases and doubles. Wagner's only top-five finish in the major hitting categories all-time is fourth in triples.

Players' Rights and the Federal League:

Iron Fist Of Owners Though players began to enjoy better conditions following A.G. Spaulding's ascension to ownership, owners still controlled the game with an iron fist in its early history, giving players few rights. Ban Johnson, president of the American League, dictated players' actions regardless of their protests, rarely bending to their requests or pleas. Star players were sometimes coddled, but more often than not, the only thing that could sway a Johnson decision was overwhelming public outrage.

Fraternity of Professional Base Ball Players After the 1912 season, a group of ballplayers, including some of the game's biggest stars like Cobb and Walter Johnson (a pitcher for the Washington Senators), formed the Fraternity of Professional Base Ball Players. However, initially, the owners simply ignored the Fraternity. This disregard for players' voices helped lead to the foundation of the Federal League in 1913, formed by a group of businessmen hoping to get in on the success of the game. The Federal League sought to poach players from the majors by promising them bigger money and the chance to become free agents. The Federal League, made up of eight teams, lasted for two seasons. In order to help drive out the Federal League, owners agreed to recognize the Fraternity of Professional Base Ball Players and agreed to a few demands: owners now paid for uniforms, the outfield fences were painted green so batters could see the ball better and not get hit as often, and salaries were raised, at first for star players, and later for all players. Ty Cobb's salary, the highest in baseball, increased from $12,000 to $20,000 in the first season of salary hikes (which, in today's dollars, would have been a salary of $441,000 dollars). However, once the Federal League died out, owners began to ignore the players again, in many cases reverting their salaries back to pre-Federal League levels, and in some cases lowering them even further. The Federal League and the Fraternity flared out, and poor conditions continued, which many believe helped lead to the game's first true black mark.

The Black Sox:

Black Sox Gambling Scandal There has never been a more famous case of gambling in baseball than the "Black Sox" scandal (though Pete Rose would come close in later years). Gambling in the game was not new by the time the game reached 1919; players and gamblers commonly associated, and even single games had been "thrown," lost intentionally by players to help them (and gamblers) make money. However, the 1919 White Sox did something considered far worse at the time: they threw the World Series. Eight players, led by second baseman Chick Gandil, worked with gambler Joseph "Sport" Sullivan to earn $100,000 dollars to throw the series against Cincinnati, a series in which the White Sox were heavily favored. In today's money, the White Sox threw the series for over $1.2 million. Gandil got seven of his teammates to go along with the plan, though convincing them wasn't difficult; their owner, Charles Comiskey, was one of the most tightfisted owners in the league, even refusing to pay to have the team's uniforms washed (which led to the nickname "Black Sox"). Eddie Cicotte, a White Sox pitcher and one of the players who threw the series, had been promised a $10,000 bonus for winning 30 games in 1919; when he reached 29 wins, Comiskey ordered him benched so as to prevent him from reaching 30. Gandil did not have to work hard.

Shoeless Joe Jackson One of the players who went along with the plan was Joseph Jefferson Jackson, known as Shoeless Joe because he once, in a minor league game in the beginning of his career, wore only socks due to the tightness of his new shoes. Joe Jackson was one of the biggest stars of the day, a hitter almost beyond compare. His lifetime average of .357 is third highest to this day. Even in the World Series, Jackson hit .375, drove in 6 runs and had 12 hits, a series record. Still, he took the money, and was thought by many to fail to catch balls he should have had, and make poor throws in from the outfield.

1919 World Series Thrown By Black Sox Though the players were promised so much more money, in the end the gamblers screwed them, paying a sum of only about $20,000 - two of the players involved in the fix never got any money at all. As the series went on, and the money stopped coming, the eight players decided to go ahead and try to win the series; however, after New York gambler Arnold Rothstein, known as Mr. Bankroll, sent a goon to threaten pitcher Lefty Williams and his wife, Williams lost the deciding game in the series.

Probe Into Game Fixing Starts After the Series ended, cries of foul play abounded, particularly from New York World reporter Hugh Fullerton. However, Ban Johnson and the owners publicly denounced the claims, dismissing them out of hand, though in private they were concerned about the merits of the accusation. When the 1920 season began, other teams began to get closer and closer to gamblers, with widespread rumors of thrown games by players on at least six teams. A Cook County grand jury was impaneled in September of that year to look into reports the Chicago Cubs had thrown a three-game series against the Philadelphia Phillies. That probe was widened to include the White Sox 1919 World Series. Eddie Cicotte was the first of the Black Sox to admit to the grand jury what they had done; Joe Jackson did the same. Chick Gandil, the orchestrator, never admitted to anything. However, the prosecutors could not produce enough evidence, and all men were acquitted.

8 Players Banned For Life Still, the scandal had rocked the country, and baseball's owners sought to repair some of the damage. They scrapped the old system of a three-person commission running baseball in favor of a single commissioner. Though many people were considered - including former president William Howard Taft, a great fan of the game - the owners went with Kennesaw Mountain Landis, a federal judge. One of Landis' first acts as commissioner was to ban all eight men from the game for life, a ban which holds to this day (meaning Jackson cannot enter the Hall of Fame).

The Era of the Hitter:

First Fatality 1920 saw the game's first fatality; Ray Chapman of the Cleveland Indians was hit in the head by a pitch, and died the next day. This tragedy spurred baseball to outlaw the doctoring of its balls. Prior to the rule, baseballs were scuffed, spit on, blackened with tar and licorice, sandpapered and scarred. Now, as soon as ball got dirty, the umpire had to replace it with a new one - a practice that continues today. The balance of power in baseball shifted from the pitcher's mound to the batter's box. With this shift arose a new star in baseball, one whose fame would eclipse all others to that point in history.

Babe Ruth George Herman Ruth began his career in 1914 as a pitcher for the Boston Red Sox. The man they called "Babe" was the best in the league, winning 89 games over six seasons. In 1919, the Sox shifted him to center field so he could hit more often, as he was a home run hitter the likes of which the game had never seen. And then, "The Trade." The Red Sox owner, Harry Frazee, had been selling off his players to the New York Yankees as a way to make cash to finance Broadway productions. Babe Ruth became a casualty of the fire sale in 1920, selling for $120,000, almost $1.3 million today. The price wasn't nearly high enough - the trade helped cripple Boston and elevate the Yankees, and Ruth began slugging home runs in record numbers. In 1920, his first season with the Yankees, Ruth hit 54 home runs, more than all but one team in the entire league. Ruth's star burned brighter than any of his predecessors, largely because home runs drew crowds (and still do). Ruth had become the game's first megastar, making more money than any player before him, primarily through endorsements; Babe pitched everything from breakfast cereal to soap to Girl Scout cookies. In 1923, the Yankees opened a new ballpark, Yankee Stadium, and Ruth, coming back from a disappointing 1922 season marred by numerous suspensions for his conduct on and off the field, hit a home run in his first at-bat. The stadium was forever after known as "The House That Ruth Built." With Ruth's success, he had ushered in an era which favored the power hitter, rather than the game of bunting, stealing and the hit-and-run.

Reaping the Crops from the Farm:

Major League Teams Buy Up Minor League Teams For Cheap Though the revolution of power hitting in baseball shook the game to its core, changing it forever, it was quite possibly not the most monumental change the game saw in the 1920s. An executive with the St. Louis Cardinals organization was struggling to put together a decent team; because the club was strapped for cash, they couldn't sign players out of the minor leagues, and often had to trade multiple players in return for just one, as a way to make some cash. In order to try and solve this problem, the executive began buying up minor league teams and funneling the most promising players to his major league squad, baseball's first farm system. Many of baseball's leaders thought the practice a disgrace - Kennesaw Mountain Landis declared it "un-American." However, the rest of the major league teams had all done the same thing. By the mid-20s, three out of ten major leaguers came up through the farm system. The Game had been changed forever. The irony is, the man who came up with the idea, Branch Rickey, is barely remembered for this remarkable achievement; rather, he is only remembered for signing a player named Jackie Robinson to play in the big leagues years later.

The 1927 Yankees:

Maybe The Greatest Team In Baseball History Any history of the game must include a special mention of the '27 Yankees. Considered by many to be the greatest team in the game's history, the Yankees won 110 games, boasting one of the most impressive rosters of all time. That season, Ruth hit 60 home runs, a record which would stand for 34 years until another Yankee broke it. Ruth earned $70,000 that year, $865,000 in modern figures. But the Yankees that season weren't all about the Babe. The '27 squad also included their "Murderer's Row," Earle Combs, Bob Meusel, Tony Lazzeri, Babe Ruth, and Lou Gehrig. Gehrig played in Ruth's shadow, but was every bit the ballplayer. Gehrig held the record for most consecutive games played (2130) for over 65 years until it was broken by Cal Ripken, Jr. in 1995. Nicknamed the "Iron Horse," Gehrig played until 1939, when he was forced to retire, having been diagnosed with ALS, a fatal neurological disorder. The disease is now commonly referred to as "Lou Gehrig's Disease."

The Depression:

Falling Attendance Just as the game was reaching its peak in the 1920's (and, some would argue, America as well), Wall Street collapsed, and the Great Depression consumed the country. Though baseball never shut down, it wasn't immune to the problems of the Depression; attendance fell as sharply as the stock market had - the tickets were still only 50 cents, but people simply couldn't pay that much for entertainment. Players' salaries fell as well, and more and more people were trying out for teams, with the hope of making a few dollars.

Gashouse Gang Despite the struggles of the nation, the '30s saw plenty of talent across baseball. The Yankees, though older, were still a force, and the St. Louis Cardinals in the National League strung together some of their best seasons, including the 1934 "Gashouse Gang," a collection of colorful personalities unlike any in baseball at the time. The team was led by pitching duo Dizzy and Daffy Dean, brothers who won a combined 49 games that year.

Game Takes Off In Japan The '30s also saw the growth of the international game, particularly in Japan, where a group of American all-stars (led by Babe Ruth) toured the country, playing 18 games against Japanese teams. The success of the tour sparked the creation of the first professional baseball league in Japan, setting the stage for a long history of talent coming in and out of the Land of the Rising Sun.

National Baseball Hall of Fame Around the same time, in 1936, baseball (and notably National League president Ford Frick) set about establishing a National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York. Cooperstown was chosen because it was said to have been the site of the creation of the game by Abner Doubleday. The first Hall of Fame class, the class of '36, was made up of Ty Cobb, Honus Wagner, Walter Johnson and Christy Mathewson (two of the game's great pitchers) and Babe Ruth, who had retired the previous season.

Joe DiMaggio It was also a time when many of the games biggest names had died or retired, leaving many to wonder about the star power of the game in the midst of the Depression. However, 1936 saw two new players step up to the stage to take the mantle from their predecessors. The first was Bob Feller, a 17-year-old kid who broke into the big leagues with the Cleveland Indians, striking out 15 St. Louis Browns in his first game and 17 Philadelphia A's just a few weeks later, a then-American league record. The second rookie broke in with the Yankees, the season following Ruth's retirement. He was an outfielder who seemed to hit everything thrown at him - Joe DiMaggio. "Joltin' Joe" would become one of the all-time greats, helping lead the Yankees to four straight championships in his first four seasons (along with, of course, Lou Gehrig).

Night Games Begin Because of struggles with attendance during the Depression, owners sought new ways to draw crowds. Larry McPhail, general manager of the Cincinnati Reds, came up with two ideas that not only helped sell tickets, but revolutionized the game. First, he put up lights at Crosley Field, where the Reds played, so the team could have night games. With the next ten years, every ballclub in the nation would have lights (with the exception of the Chicago Cubs, who wouldn't install lights in Wrigley Field until 1988). Additionally, McPhail started having games broadcast live on the radio. Radio broadcasts of baseball games helped sell tickets everywhere they went, and became the standard for the game in America.

To War:

Ted Williams As the Depression wound down, and with world war on the horizon, baseball nevertheless marched on. Gehrig retired in '39, died just two years later, and the game had once again lost one of its brightest stars - but joining the league in '39 was a rookie whose hitting process arguably surpassed anyone who had come before him. Ted Williams, a 21-year-old from San Diego came up to the big leagues with the Boston Red Sox, and in his first year with the club hit .327 with 31 home runs and 145 RBIs, one of the best rookie seasons in history. When his career ended, "Teddy Ballgame" had the fifth highest batting average ever (.344), and in 1941, hit .406 in a single season, the last player to do so to this day. In that same year, Joe DiMaggio, now one of the game's biggest stars, completed one of the greatest feats in modern baseball history, one considered unlikely ever to be matched at the big league level. On May 15, DiMaggio got a single in a game against the Chicago White Sox. DiMaggio then hit safely in the next 55 games. His 56 game hitting streak has remained unbeaten to this day.

Baseball Stars Join The Army However, baseball's talent pool took a dip for the next few years, as the U.S. entered World War II and some of the games biggest names traded their uniforms for those of the army and navy. Bob Feller joined up one day after the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor; Joe DiMaggio volunteered for the army, and Ted Williams became a navy pilot. Though Commissioner Landis asked President Roosevelt if the game should shut down during the war, the president insisted it continue. Former players, long retired, came back to play while the current crop fought overseas.

All-American Girls Professional Baseball League Additionally, Phillip Wrigley, owner of the Chicago Cubs, started up the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League, getting softball players from around the country to convert to hardball and play for one of the four initial teams, which later expanded to 10. The girls were not only required to be good ballplayers, that had to be "irreproachably feminine," attending charm school and required to wear skirts, high heels and makeup off the field.

As the war began to wind down, and the game slowly turned back to normal, it would quickly be turned on its head once again - this time, not by war overseas, but by integration.Branch and Jackie:

Branch Rickey In November 1944, Kennesaw Mountain Landis, the game's first commissioner, died, leaving behind a legacy of repairing thew game after the 1919 Black Sox scandal and pursuing a policy, at all costs, of keeping black players out of the game. His replacement, Albert "Happy" Chandler, reversed the public policy of Landis, saying he felt African-Americans had every right to play . Fifteen out of sixteen owners, however, disagreed with him; the lone exception was Branch Rickey, who had recently bought the Brooklyn Dodgers. Rickey decided he was going to strike first and bring up a black player to the bigs, particularly since there was no rule in place disallowing it - it had always been an unwritten rule of baseball. Rickey scoured the country, trying to find right player; he found him in the likes of Jack Roosevelt Robinson, a 26-year-old Georgian who lettered in four sports at UCLA (the first athlete to do so). Rickey decided on Robinson not just because he was a great ballplayer, but because Robinson carried himself with a determination that was important to the cause of integrating baseball.

Jackie Robinson On April 9, 1947, after spending a year on Brooklyn's minor league squad, the Montreal Royals, Jackie Robinson signed a contract to play first base for the Brooklyn Dodgers. On opening day, April 15, Robinson officially broke the color barrier in baseball, becoming the second black player ever to play in the majors - Moses Fleetwood Walker had made a short appearance for Toledo of the American Association in 1884. But Robinson was the first to make it in MLB, and the game never looked back - though many at the time wished it had. Robinson endured untold amounts of abuse from fans and fellow players alike. Still, he never retaliated in the early years, something Rickey insisted on, telling Robinson any violent response would set the cause back twenty years. In the American League, Larry Doby was signed by Bill Veeck to play for the Cleveland Indians, and the shortstop became the first African-American to play in the AL.

As the forties came to a close, the game enjoyed its greatest success to that point, setting records for attendance, drawing more than 21 million fans. But the fifties would only spread the game farther.

New York and the West:

New York Yankees, Giants and Dodgers The Game in the '50s belonged to New York, which at the time had three teams, the Yankees in the American League and the Giants and Dodgers in the National League. Between 1949 and 1958, the World Series featured at least one New York squad, and six times had two. One of the years when two New York teams played in the series, 1951, was more famous for its National League championship play-off series. The Giants and the Dodgers, bitter rivals in the Empire City, tied for first in the NL at the end of the season, and played a three-game series to determine who would play the Yankees for the title. Tied a game apiece, and down 4-1 going into the final inning, the Giants stormed back, with Bobby Thompson hitting a game-ending three run homer called "The Shot Hear 'Round the World." Few remember that the Giants went on to lose to the Yankees in the World Series.

Mickey Mantle DiMaggio retired in December of '51, but, in what was becoming a pattern in baseball, and particularly with the Yankees, a replacement star was stepping up to the plate. Mickey Mantle, a rookie in DiMaggio's final season, took over Joltin' Joe's spot in center field for the Bronx Bombers. At the end of his career, Mantle would find his place alongside DiMaggio as one of the greatest Yankees of all time. Still, his career was somewhat tumultuous; he was often injured, and because such high expectations were placed on him (Mantle himself said he was expected to be "Ruth, Gehrig and DiMaggio, all rolled up into one"), he was often booed by Yankee fans anticipating near-perfection.

The Effect Of Television On The Game But with New York domination, baseball as a whole suffered. The '50s saw a shift in the country out of the eastern cities to the suburbs and the West Coast, a region that had no big-league ballclubs. Additionally, the advent of television was thought by many to have a negative effect on the game. While radio had increased attendance for the teams that used it, television was decreasing attendance. Owners scrambled to find ways to draw people to the ballpark, and none was more inventive than Bill Veeck. As general manager of the Indians, he signed Larry Doby and Satchel Paige, the great Negro Leaguer, to break the color barrier in the AL. Helming the Chicago White Sox, he installed an exploding scoreboard that shot off fireworks for home runs and victories (a gimmick still employed by the White Sox today). Running the St. Louis Browns, Veeck came up with some of his best work. His publicity stunts with the Browns included Grandstand Managers' Day, in which fans were given placards that said things like "Bunt," "Steal" and "Yank the pitcher," and the on-field manager was forced to obey, and signing Eddie Gaedel for one day. Gaedel stood 3 feet, 7 inches, with a strike zone that measured just one and a half inches. Gaedel pinch hit, walking on four straight pitches, then was pulled for a pinch runner.

Teams Move Around The Country But Veeck's little tricks didn't do enough, and baseball's landscape began to change. The Browns abandoned St. Louis for Baltimore and became the Orioles. The Philadelphia A's moved to Kansas City, while the Boston Braves moved to Milwaukee. But the '50s were not wholly a time of despair for MLB. The '50s saw the advent of a player who would be considered by many the best to ever play the game - both before and since. Willie Mays, who broke in with the Giants in 1951, would go on to hit .302 for his career, winning 12 Gold Gloves for best fielder at his position, hit 660 home runs (fourth on the all-time list) and become the first player to hit 300 home runs and steal 300 bases. Players, managers and fans alike heaped praise on the young centerfielder.

Teams Go West The '50s also saw the beginning of the great migration west, not just by America, but by baseball. In its history, the furthest team west played in Missouri - until 1957. It was in that year that Walter O'Malley decided he wanted to move out of Brooklyn, and found a willing home in Los Angeles. He convinced New York Giants owner Horace Stoneham to go with him, moving the Giants to San Francisco. New York was no longer the baseball capital of America, and baseball's westward expansion had truly begun.

The 1960s:

New Bigger Shinier Stadiums As much as the '50s saw great changes in baseball, the game's transformation only became more complete in the next decade. The old game, played by legends like Ty Cobb and Babe Ruth, was disappearing. The old ballparks - Ebbett's Field, home of the Dodgers, Sportsman's Park in St. Louis, Pittsburgh's Forbes Field, Philly's Shibe Park and Crosley Field in Cincinnati, all historic sites, were torn down, making way for newer, shinier stadiums.

Mickey Mantle and Roger Maris Even records were falling, notably those of Babe Ruth. During the World Series in 1961, Whitey Ford of the Yankees threw 33 2/3 scoreless innings in a row, eclipsing the Babe's mark. But it was a chase for another record during the '61 regular season that got all the attention. Mickey Mantle and Roger Maris, both of the Yankees, battled in a season-long race for 61 home runs, a mark that would top Ruth's record of 60. On the final day of the season, Maris hit a home run to the right field bleachers in the fourth inning, setting a new single-season home run record, one that would stand until 1998.

Branch Rickey Branch Rickey, in one last attempt to continue revolutionizing baseball, tried to start up a new league, the Continental League, putting teams in cities without baseball (and two teams back in New York). The other owners cut him off at the pass, agreeing to expand each league by two teams and increasing the length of the regular season from 154 games to 162 (which is where it still stands today). The Sixties saw both expansion and shift: the Los Angeles Angels sprouted up in 1961, moving to Anaheim five years later, becoming the California Angels (and much later the Anaheim Angels, and most recently the Los Angeles Angels of Anaheim). In 1962, two new teams joined the National League - one, based in Houston, the Colt .45s, became the Astros just a few years, the other in Queens, the New York Mets. The Washington Senators moved to Minnesota and became the Twins in 1961. In 1966, the Braves moved once against, this time from Milwaukee to Atlanta, where they remain to this day, and in '68, the Kansas City A's also relocated for the second time, shifting now to Oakland, their permanent location at present.

Pitcher Rule Changes and The Slider The decade also saw a shift in something other than location. Just as the 1920s saw dominance transfer from the pitchers to the hitters, that balance reverted back to pitchers in the '60s. Commissioner Ford Frick urged the owners to vote on rule changes to benefit pitchers; the owners re-expanded the strike zone to stretch from the top of the shoulders to the bottom of the knees. Pitchers developed a new pitch, the slider, which started out looking like a fastball but tailed away from the hitter. More night games made it harder for hitters to see the ball, and new, bigger gloves made fielding easier. In one season, 1962, homers dropped 10 percent, the number of runs scored dropped 12 percent and the overall batting average lowered by 10 points. This shift helped catapult Sandy Koufax to stardom. A Jewish ballplayer who refused to play on Yom Kippur or Rosh Hashanah, Koufax had already pitched seven years in the big leagues coming to 1962 with little acclaim or great success. As he changed his pitching style - and the league helped out its pitchers - Koufax became an ace, winning five ERA (earned-run average) titles, pitching four no-hitters and winning the Cy Young award three times over five years. Facing Koufax, said Pirate great Willie Stargell, was "like drinking coffee with a fork." Unfortunately, those five years were the last he'd pitch in the majors, his career cut short by injury.

Baseball Moves Inside Additionally, the 1960s saw the game move indoors. When a team sprouted up in Houston, public funds in the amount of $31.6 million dollars (today, $224 million) built the Harris County Domed Stadium, more commonly called the Astrodome. At first, it was a disaster - players got balls lost in the ceiling, and the grass died. Soon, though, some of the skylights were painted over, and a new creation called Astroturf (a plastic surface held together by zippers) kept the Astrodome around for years to come.

The Union:

Players Association Marvin Miller was an economist with no connection to baseball other than as a fan of the game. He had worked for the government for a time before working with the machinists union, the autoworkers union and steel workers union. In 1965, pitchers Robin Roberts and Jim Bunning approached him, asking him to become the executive director of the Players Association, an organization that had been in existence since 1953, but had done precisely nothing for players in that time. Miller agreed, and was overwhelmingly elected. Right away, he set out to finally equalize the relationship between players and owners. Before Miller came along, players had few rights; they had no say in how their pension fund was run, owners refused to bargain collectively, the minimum salary had only gone up $2000 over a twenty year period between 1946 and 1966 (in a time when inflation skyrocketed) to $7000 (which equals roughly $43,000 dollars today), and the reserve clause was in effect, meaning a player couldn't leave his team for another unless his team allowed him to do so (generally via a trade). Within one year, Miller had gotten the owners to contribute a lot more money to the pension fund, agree to better working conditions, and raise the minimum salary to $10,000. But Miller was far from done working.

New Teams Added and Divisions 1969 was perhaps the greatest single year of change in the game. Despondent at the domination of pitchers (and because hitters drew crowds), owners once again changed the rules, lowering the pitching mound and shrinking the strike zone again. Four new teams were added - in the American League, the Kansas City Royals and the Seattle Pilots (who after only a year became the Milwaukee Brewers), and in the NL, the San Diego Padres and the Montreal Expos. With those additions, the leagues split into divisions for the first time ever, creating two new playoff series: the National and American League Championship Series. And '69 saw Marvin Miller lead a holdout of players, with owners giving in to some of his demands, including an even greater increase in pension fund donations and allowing benefits to be extended after four years of service in the bigs, rather than five. It was the start of a significant loosening of the owners' grip on the game.

Players Reserve Clause As the 60s gave way to the 1970s, players and Miller worked harder and harder to end the use of the reserve clause. One player, Curt Flood, after asking for a raise from the owner of his team, the St. Louis Cardinals, was told he was being traded to the Philadelphia Phillies, a team whose fans were notoriously hard on black players. Flood, an African-American, did not want to leave St. Louis, and wrote a letter to commissioner Bowie Kuhn stating he would not play for Philly. When told he had no choice, Flood then proceeded to take his case to court, with his suit reaching the highest court in the land. Unfortunately, Flood's challenge to the reserve clause was denied 5-3. However, owners felt more and more pressure from players, and instituted the 10 and 5 rule, which said any player with 10 years experience in the major league, including 5 years with his current team, could veto a trade.

1972 Players Strike Still, the players had had enough, and in 1972, every MLB player went on strike, the first players strike in sports history. The owners retaliated, releasing or trading sixteen of the twenty-six player representatives with the Player's Association. The strike ended with the owners giving in to Miller's original demands - a cost-of-living raise in pension and welfare benefits. But Miller wasn't done; a year later, he got the owners to agree to arbitration hearings by a three-person panel over salary disputes. It was this avenue that allowed Miller to finally defeat the reserve clause.

Players Wages Increase The reserve clause's language stated that if a player and his club couldn't agree to a contract, the club could "renew the contract for the period of one year on the same terms." Owners had always taken this to mean they could simply continue to renew the contract, year after year. Miller argued it could only happen for one year, and then the player would be released. Miller got two pitchers - Andy Messersmith of the Dodgers and Dave McNally of the Expos - to agree to test his theory in 1976 and go to arbitration. The owners' attempt in court to block the arbitration hearing was denied, and the arbitrator ruled in favor of the players. The owners again went to court to try to reverse that decision, and again were denied. Miller shrewdly stepped in with what appeared to be a compromise - players had to serve six years in the league before becoming eligible for free agency, rather than possibly becoming free agents every year. The owners quickly agreed, but it was Miller and the players who ended up with the better end of the deal; but only having a few players come into free agency every year, the value of those free agents went much higher. The average salary for ballplayers doubled the next year and tripled over the next five years.

Free Agents The Game would never be the same again, particularly financially. George Steinbrenner, the late owner of the New York Yankees, was among the first to see the value of free agency, and spent previously unseen amounts of money on the best players he could find on the market. His Yankees won the AL in 1976 and the World Series in '77 and '78. Steinbrenner was something of a unique owner - he changed managers 18 times in his first 17 years, including hiring and firing one man (Billy Martin) five different times - but his actions as owner set the tone for baseball all the way to the present, as the gap between the teams that can spend large amounts of money and the teams that can't widens.

Hammerin' Hank:

Henry "Hank" Aaron Amidst all the labor negotiating going on behind the scenes and in public, on the field, one man was turning heads: Henry "Hank" Aaron. Aaron had come into the league in 1954 for the Milwaukee Braves, moving with the team to Atlanta. When he retired, he had played 23 seasons, and ended up with the most RBIs in major league history (2297), a record he still holds. But the record he held that truly drew the attention of the nation was his run at a record held by the Babe.

Hank Aaron and Babe Ruth Babe Ruth was a home run hitter of unparalleled power; he didn't just hit home runs, he crushed them. He led the league in home runs 12 times in his career, more than almost any other player in history. The size of his home run totals was surpassed only by the size of his personality. Hank Aaron, on the other hand, was a quiet, unassuming person. While he could hit the long ball, his home runs were rarely greeted with the kind of awe the Babe's had received. Ruth was all about strength; Hank was all about bat speed, getting his wrists around on the ball quicker than anyone else. Aaron led the league in homers only four times in his career. The Babe hit more than 45 home runs in one season nine times; Aaron only accomplished that feat once. Aaron was also black.

Hank Aaron Beats Babe Ruths Record As the 1974 season began, Hank was one home run shy of tying Babe Ruth's career home run record. By the end of 1973, he had received more mail than any other single person in the country who wasn't president of the United States. Unfortunately, a good portion of that mail was not in support of the great ballplayer. A black man trying to top a white man's record had never been popular in America; doing it in Georgia didn't help matters. Aaron received countless death threats, his children in college threatened with kidnapping. Guards escorted him to and from every ballpark. Yet, Aaron remained stoic, never getting mad. He merely went about the business of hitting home runs. On Opening Day 1974, playing in Cincinnati, Aaron hit the record-tying home run in his first at-bat of the season. Just a few days later, on April 8 in Atlanta, Aaron hit home run number 715 over the left field wall. When all was said and done with his career, his total would be 755, and would stand for over 30 years.

"The Business of Caring":

Cincinnati Reds and the Boston Red Sox 1975 World Series Despite Aaron's feat, the product on the field in the first part of the '70s was thought by some to have waned; public polls showed that Americans were losing interest in the game. Then came the 1975 World Series between the Cincinnati Reds and the Boston Red Sox. The Reds, the game's first professional team, hadn't won a championship in 35 years; the Red Sox, a team with their own storied history, hadn't won a title in 57 years. The Reds, nicknamed "The Big Red Machine" were considered by many to be one of the greatest teams of all time, a team that might have even challenged the '27 Yankees. Led by Hall-of-Famers Joe Morgan, Tony Perez, Johnny Bench and legendary would-be Hall-of-Famer Pete Rose, the Reds rolled through the National League, an unstoppable force of the old-fashioned variety. The Red Sox had their own roster of all-stars and Hall-of-Famers, led by grizzled veteran and Boston legend Carl Yastrzemski with rookies Fred Lynn and Jim Rice. The series went into game six in Boston with the Reds one game from the championship. The game itself was tied 6-6 going into the twelfth inning when fan favorite (and Hall-of-Famer) Carlton Fisk came to the plate to the plate. He hit a long fly ball right down the foul line; Fisk went jumping up and down the line to first base, waving his arms, willing the ball fair, and went it hit the foul pole (which, ironically, made it fair), he thrust his arms into the air in exultation, having sent the series back to Cincinnati for the final game. The historic game six drew viewers to their TVs for game seven, creating a 75 million-person audience for the deciding game, the largest viewership for a sporting event at the time.

The Fisk home run led to this passage from author Roger Angell:It is foolish and childish, on the face of it, to affiliate ourselves with anything so insignificant and patently contrived and commercially exploitive as a professional sports team, and the amused superiority and icy scorn that the non-fan directs at the sports nut (I know this look -- I know it by heart) is understandable and almost unanswerable. Almost. What is left out of this calculation, it seems to me, is the business of caring - caring deeply and passionately, really caring - which is a capacity or an emotion that has almost gone out of our lives. And so it seems possible that we have come to a time when it no longer matters so much what the caring is about, how frail or foolish is the object of that concern, as long as the feeling itself can be saved. Naïveté -- the infantile and ignoble joy that sends a grown man or woman to dancing and shouting with joy in the middle of the night over the haphazardous flight of a distant ball -- seems a small price to pay for such a gift.

Baseball, in the mind of Americans, had returned.

Pete Rose Record With two championships under his belt (winning again with Philadelphia in 1980), Pete Rose could easily have retired after a monumental 17-year career. But he wasn't done yet, principally with the record books. Rose, nicknamed "Charlie Hustle" early in his career, had always looked up to Ty Cobb, and his goal now was to best Ty Cobb's record of 4,191 hits. In September of 1985, near the end of his 23rd season in the majors, Rose singled in a game against the San Diego Padres. It was hit number 4,192, a new major league record. When he retired the next year, he had collected 64 more, finishing with a still-record 4,256.

Baseball's Black Marks:

Massive Players Salaries and 1981 Strike While milestones were chased and reached on the field, Marvin Miller and the owners continued their vicious battle for control of the game. In 1981, the players once again went on strike, this time protesting the owners' call for compensation, be it in cash or with players, for players who left teams in free agency. The players once again held firm. However, public perception began to turn against the players, at least somewhat. The tide turned as television revenues continued to rise, increasing players' salaries. By 1994, players earned 50 times what the average person earned, compared to eight times what the average person earned in 1976 (and just seven times what the average person earned way back in 1869).

Owners Collusion In 1985, several top free agents failed to get offers from anyone other than their most recent teams. Miller smelled a rat, charging the owners with collusion. An arbitration panel was assembled, eventually finding the owners guilty of collusion in free agency, ordering them to pay $250 million in damages to the players. Once again, Miller had triumphed.

Players Loss Of Faith By Public However, as players won victories against the owners, they were starting to lose battles in public relations, as drugs became a major issue in the sport. While drinking had always been acknowledged as simply part of the game, and largely ignored, the growing drug problem, particularly with cocaine, became something the league - and the public - could not ignore, and it stained many legacies, as well as cut several promising careers short.

Pete Rose Gambling Scandal But perhaps the biggest blow came not from drugs or alcohol, but gambling. Pete Rose, a national icon of the game, one of the most well-respected ballplayers of his time (or arguably any other), was accused of excessive gambling, and even betting on games in which his team played (primarily when he was a manager). Commissioner Bart Giamatti banned Rose from baseball for life, just as Landis had once done to the eight White Sox players.

1994 Strike:

1994 Players Strike Once again, the owners and players could not come to an agreement, this time over a new collective bargaining agreement, and specifically the issue of a salary cap. The player's union, now headed by Donald Fehr, went on strike in August of 1994, causing the cancellation of the rest of that season, and, for the first time in history, the World Series. The two sides still couldn't agree when the 1995 season began, but a judge issues an injunction, putting the players back on the field under the old contract. The collective bargaining agreement finally went into place in 1997, putting in place revenue sharing and a luxury tax, both of which were intended to curtail runaway spending by teams, as well as lessen the gap between the highest spending and lowest spending teams. It failed to do any of that. The Games highest team salary in 1997 belonged to the New York Yankees, with a total number of $73.4 million spent on its players. The lowest total salary belonged to the Oakland A's, at just under $12.9 million. Ten years later, in 2007, the Yankees still had the highest total salary, now at $189 million dollars, and the lowest salary belonging to the Tampa Bay Rays, with a total salary of $24 million. Those numbers only go up, and the gap only widens.

Fans Fed Up With Players and Owners Attendance Drops 20% But perhaps the most troubling result of the 1994 strike was its impact on the fans. Turned off by the obscene amounts of money being quibbled over, many fans turned away from the game. The average attendance fell 20 percent from 1994 to 1995, and didn't reach pre-strike levels until over ten years later. However, two catalysts helped bring back some fans, and both involved some lofty records.

Cal and The Chase:

Cal Ripken, Jr In 1995, fans slowly began to pay attention to the national pastime as Cal Ripken, Jr., a shortstop/third baseman for the Baltimore Orioles inched closer to Lou Gehrig's consecutive games played record, a mark thought by many to be untouchable. Yet, as the season went on, Ripken got closer and closer. Finally, on September 6, after the first half of an inning between the Orioles and the California Angels was played (and the game became official), Ripken had set the record. When he finally missed a game in 1997, he had played 2,632 games, a record which today is believed will never be broken.

Sammy Sosa and Mark McGwire Chase For The Record But while Cal's chase of history helped bring baseball back somewhat, in the summer of 1998, two men captivated the nation, and helped restore the shimmer to the star of the game in America. Sammy Sosa and Mark McGwire, respectively of the Chicago Cubs and St. Louis Cardinals, spent the year engaged in a home run race seen only once before, in 1961 between Maris and Mantle. This time, however, they were not chasing the Babe, but Maris. Ironically, the chase did not begin as much of a contest - in May, while McGwire had already racked up 24 home runs, Sosa was only at nine. However, the greatest home-run hitting month of all time catapulted Sosa into the race, as he hit 20 home runs in June. The two were neck-and-neck for the rest of the year, until, on September 8, McGwire knocked home run number 62 over the wall at Busch Stadium, fittingly against Sosa's Cubs. McGwire would end up with 70 that year, Sosa with 66 (and the MVP award), both men credited by many as having saved baseball.

Bonds:

Barry Bonds Chase For The Record While McGwire and Sosa's chase for history captivated the nation, Barry Bonds identical chase did not quite happen the same way, just three years later. In 2001, Bonds ended up hitting 73 home runs, breaking McGwire's record, but did so without the same acclaim or fanfare, at least not nationally. Most attribute it to the tremendous likeability of McGwire and Sosa combined with the tremendous unlikeability of Bonds. Both with the media and to the public, Bonds, whether justly or unjustly, was considered by many to be unwelcoming to fans, arrogant and egotistical, and many decried him as a poor teammate. His detractors, however, did not deter him; not only did Bonds set the single-season home run record, he set records for highest single-season slugging percentage, consecutive MVP awards (four), total MVPs (seven), walks and intentional walks. And in 2007, Bonds set the all-time home run record, surpassing Hank Aaron's record of 755. He finished his career with 762 home runs. However, his pursuit of Aaron's record was marred not just by criticism of his character, but by the far more serious allegation of steroid abuse.

Juicing :

Widespread and Rampant Steroid Use Since the 1990s, whispers had circled baseball about the use of performance-enhancing drugs, though those whispers were not very loud and rarely acknowledged by the media or the public. However, with the release of the 2005 book Juiced by former major leaguer Jose Canseco. The book shook the foundations of the sport, as Canseco alleged widespread and rampant use of steroids. Congress held hearings, the FBI continued running investigations, and public perception of the so-called "steroids era" became worse and worse.

Testing Introduced 2005 Bending to public outcry and excoriation in the media, commissioner Bud Selig cracked down on the use of performance-enhancing drugs in the game in January of 2005, expanding the list of banned substances, instituting mandatory year-round testing for all players and introducing suspensions for positive tests: 10 days for first-time offenders, 30 days for a second suspension, 60 for a third and one year for a fourth. In less than a year, the game had toughened their policy, adding testing for amphetamines and lengthening the suspensions to 50 games (not days) for a first offense, 100 for a second and a lifetime ban for the third.

Mitchell Report Four months later, Selig announced that former senator George Mitchell would lead an investigation into steroid use in baseball, encouraging teams and players to cooperate in any way possible (though lacking the authority or muscle to require participation). Over a year and a half later, the Mitchell Report was released, a 311-page document detailing the expansive use of performance-enhancing drugs for over a decade and naming over 45 players who used these drugs.

Big Stars From 90's and 00's Implicated In the end, over a hundred players have either been implicated in steroid use, or admitted to using PEDs in their careers, including Bonds, Sosa, McGwire and plenty of other stars from the '90s and '00s.

College Game

While the earliest history of the game details a side-by-side development with college baseball, the professional game left college in its wake. While the College World Series is televised yearly, it doesn't receive nearly the kind of ratings that even much regular season gets. With a much higher percentage of its players from foreign countries, and with a minor league system in place that allows players to forego college, baseball has far less of a need for a vibrant collegiate game than its counterparts in football or basketball; the closest comparison is to hockey, which fields the same high percentage of foreign players and a vast minor league system which eschews the necessity of college. The College Baseball Hall of Fame only came into existence in 2006; the sport simply fares better on the professional stage.

The Game at Present:

Salaries are now Telephone Numbers Though the current game closely resembles its ancestor of the early 1900s on the field, off the field, it has changed dramatically. Currently, the highest paid ballplayer in the league is Alex Rodriguez of the New York Yankees, who earns $33 million a year, a sum it would take Ty Cobb 412 seasons to equal at his highest yearly salary. (Even if converting Cobb's salary to today's dollars, it would still take the Georgia Peach over 38 seasons to earn as much as A-Rod.) The owners spend well over a billion dollars on player salaries alone, and make far, far more than that in revenue. Baseball's most valuable franchise, the Yankees, is estimated to be worth over $1.3 billion dollars. Many argue over whether these gaudy numbers are good or bad for the game; regardless of whose side is right, the trends show no sign of stopping.

Game Is Slowing Down Baseball is also struggling with updating the game. Instant replay has recently been added, but only to examine home runs. Proponents of instant replay say the game is better off by making sure calls are right; opponents counter that the game has always been decided by humans and should continue to be. Additionally, the game is dealing with the lengthening of its games: while in the 1920s games typically lasted under 2 hours, by 1975 that had grown to 2 hours and 25 minutes. Currently, the average is just under 3 hours. In a world that's moving faster, the game is slowing down in almost every conceivable way. Whether or not they can catch up will determine if the national pastime will fall by the wayside of American sports.

Resources: Baseball: An Illustrated History by Geoffrey C. Ward and Ken Burns (ISBN: 978-0679404597) Bert Sugar's Baseball Hall of Fame: A Living History of America's Greatest Game by Bert Randolph Sugar (ISBN: 978-0762430246) This Day in Baseball: A Day-by-Day Record of the Events that Shaped the Game by David Nemec and Scott Flatow (ISBN: 978-1589793803) MLB History (http://mlb.mlb.com/mlb/history/?tcid=mm_mlb_news) The History of Baseball (http://www.rpi.edu/~fiscap/history_files/history1.htm) Baseball Year in Review (http://www.baseball-almanac.com/yearmenu.shtml) Historical Pitching Leaders (http://mlb.mlb.com/stats/historical/leaders.jsp?c_id=mlb&baseballScope=mlb&statType=2&sortByStat=All&timeFrame=3&timeSubFrame2=0) Historical Batting Leaders (http://mlb.mlb.com/stats/historical/leaders.jsp?c_id=mlb&baseballScope=mlb&statType=1&sortByStat=All&timeFrame=3&timeSubFrame2=0) Hank Aaron (http://www.baseball-reference.com/players/a/aaronha01.shtml) Babe Ruth (http://www.baseball-reference.com/players/r/ruthba01.shtml) Baseball Quotes (http://www.peterga.com/baseball/quotes/the_game.htm) Baseball Salaries (http://content.usatoday.com/sports/baseball/salaries/default.aspx) Baseball's Drug Policy Timeline (http://mlb.mlb.com/mlb/news/drug_policy.jsp?content=timeline) Baseball's Steroid Era (http://www.baseballssteroidera.com/) Mitchell Report (http://topics.nytimes.com/topics/reference/timestopics/subjects/b/baseball/mitchell_report/index.html) College Baseball Hall of Fame (http://www.collegebaseballfoundation.org/page/index/hall_of_fame) Faster Games (http://www.usatoday.com/sports/baseball/2003-03-05-faster-games_x.htm)Our New Sports Section and the specific sports pages were written and researched by a passionate sports fan while majoring in journalism at the University of Missouri. He is now the State News Reporter for Indiana Public Broadcasting

Follow Brandon J Smith on Twitter